Weimar, Germany is a town with an identity crisis. On one hand, it is a town deeply rooted in the Romantic Classical period. On the other hand, it is progressive, modern and gave birth to the Bauhaus movement. The dual traditions – Classical Weimar and the Weimar Bauhaus – are both recognized as separate UNESCO World Heritage Sites. I’ve visited the city several times over the last 20 years, and each time is a truly profound experience.

I would argue that this town may well be the most important city in Germany. Weimar has had the most significant impact on German (and European) culture of any city. Berlin, Munich, Frankfurt and any other city cannot lay claim to it’s seat as the cultural and intellectual capital of Germany.

And it’s all thanks to one woman: Anna Amalia.

She almost singlehandedly changed the course of events in Europe. Duchess Anna Amalia of Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel was the ninth child of an important aristocratic family. In 1756, she married the Duke of Saxe-Weimar-Eisenach, Ernst August II Konstantin.

Two and half years later, her husband died leaving her with an infant son, Karl August. Anna Amalia proved adept at filling her husband’s shoes and ruling as regent for her son for the next 17 years. Yet Anna Amalia’s love was not politics – it was art. She was herself an accomplished composer during the period when she served as

regent.

But Anna Amalia is important today for what she did here. Beginning with her reign as Regent, the age of Classical Weimar began. She envisioned her court filled with the greatest cultural and intellectual minds ever assembled. She drew luminaries from around Europe and propelled the city onto the world cultural stage.

Most notable in her court were Johann Wolfgang von Goethe and Friedrich Schiller. Their sculptures stand before the German National Theatre honoring their legacy. Later luminaries such as Franz Liszt, Richard Strauss and Friedrich Nietzsche came to Weimar.

Over 250 years later, Anna Amalia’s legacy can still be found in the city of Weimar and over 3.5 million visitors come to explore the rich culture her court left behind. I recently visited to explore the sites of Classical Weimar: Goethe and Schiller’s houses, the Royal Palace, and the City Church of St. Peter and St. Paul with its massive altar by Lucas Cranach the Elder. Collectively, a large section of the town is persevered as a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

What struck me while visiting Weimar was how profound and revolutionary this Golden Age was for the town and for the country. Exploring Weimar, no one site tells the story of the city’s importance. The homes of Goethe and Schiller individually give unique insights into their respective worlds, particularly Goethe’s home where he lived for over 50 years right in the center of town.

But the reason we have a Classical Weimar UNESCO World Heritage Site is the totality of the city’s cultural importance. Walking through Classical Weimar, you can’t help feeling like you are in some place special.

The liberal and progressive trends implemented by Anna Amalia also proved to be the seeds necessary for the Weimar Bauhaus movement. Bauhaus was both born from the liberal ideals of Classical Weimar, but can also be seen as a reaction to the idealism of that period. The key is in understanding the years after Goethe’s death.

The city continued to play an important role in German culture. By 1860, an art school had been founded in the city and “The Weimar School” of painting was born.

But Germany as a nation was locked into a rigidity that idealized and romanticized the Classical period. The Weimar Bauhaus University was born from the liberal and progressive ideals of Classical Weimar, but eschewed its dwelling on themes of the past.

The year 1919 proved pivotal in Weimar’s history. In the wake of World War II, this was the year that a new constitution for Germany was drafted in the city and The Weimar Republic was born. The year 1919 was also the official founding of the Weimar Bauhaus movement. Born out of the The Weimar School of painting, The Bauhaus School in Weimar focused on architecture and design. It’s important to understand that Bauhaus was both a physical school, but it was also a movement.

The Weimar Bauhaus movement brought function and practicality above fanciful designs and romantic whimsical elements. Bauhaus gave birth to Modernism, which drove architecture throughout most of the 20th century.

While the Weimar Bauhaus University lives on today, Bauhaus as a movement only lasted from 1919 to 1933. The free thinkers and progressive ideologies of the Bauhaus School proved too much for the right-wing National Socialism movement. The city was an early adopter of Nazi ideology. Many of the teachers at The Bauhaus School were fired and the school ultimately left for Dessau.

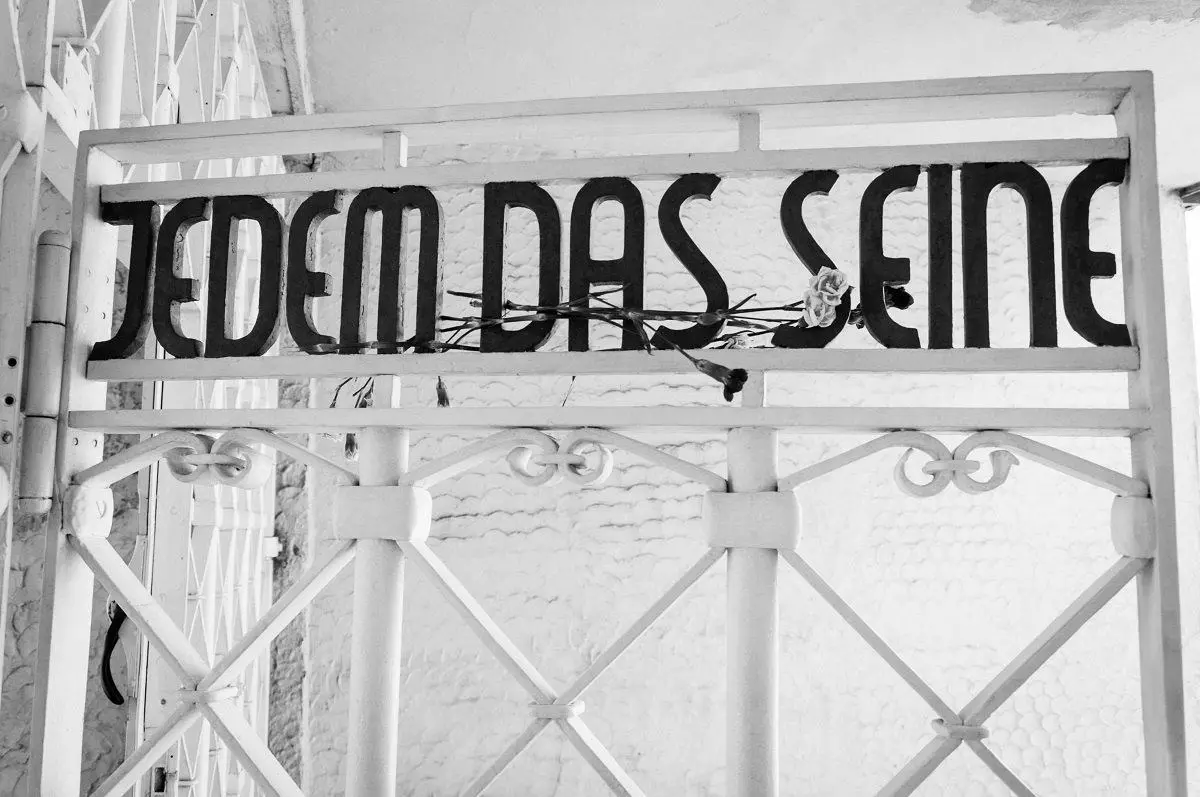

The tale of two Weimars comes together in the Nazi era. When the Nazi’s built their largest concentration camp within Germany, Buchenwald, they drew on Classical Weimar’s past. Buchenwald was built into the woods were Goethe used to walk. The concentration camp was built around the oak tree where Goethe used to write. Along with the theological works of Martin Luther, the Nazi’s drew on the works and themes of the Classical period to legitimize their regime.

Yet, despite their loathing of Bauhaus, the Nazi’s incorporated some Bauhaus design elements into the camp (including the main gate). And, some of the first people imprisoned in Buchenwald were the intellectuals who helped craft the Modern period and the Bauhaus. The Nazi’s had a special term for their works: degenerate.

Which brings me back to Anna Amalia. It’s difficult to imagine what this city or even Germany would be without her. Usually when we travel, I eventually reach a point of feeling like I’m seeing “old dead stuff.” After a while, it doesn’t matter how interesting a church or museum is, I’m ready to move on. We call it being “cultured out.” That doesn’t happen here. Everywhere you feel like you are touching her legacy.

Visiting Weimar is a lesson in history, but it is also one that captured my attention. Around every corner, I learned something new. In many cities, cultural legacies are abandoned in favor of new, popular trends. But in Germany, the echoes of Classical Weimar and the Weimar Bauhaus movement can still be heard.

While in Germany, I was the guest of the German National Tourist Board and Weimar Tourism. As always, all opinions are my own.

Lance Longwell is a travel writer and photographer who has published Travel Addicts since 2008, making it one of the oldest travel blogs. He is a life-long traveler, having visited all 50 of the United States by the time he graduated high school. Lance has continued his adventures by visiting 70 countries on 5 continents – all in search of the world’s perfect sausage. He’s a passionate foodie and enjoys hot springs and cultural oddities. When he’s not traveling (or writing about travel), you’ll find him photographing his hometown of Philadelphia.