A lonely hill in Eastern Colorado amid the sagebrush and prickly pear cactus played host to one of America’s darkest moments. This is Camp Amache, the World War II Japanese internment camp in Colorado. And it broke my heart.

Granada, Colorado feels like the middle of nowhere. And that’s probably because it is. Hours from anywhere and just a stone’s throw from the Kansas border, this was the end of the line – the old train line stopped here. This place feels like the end of the world.

The dusty hillside of the Amache Colorado internment camp is a long way from the beauty of the Rocky Mountains, with its skiing and hot springs. In fact, its worlds apart. But the Amache Camp is an extremely important part of Colorado history.

How did this desolate, horrific place come to be?

The War Relocation Authority

On December 7, 1941, a surprise attack by the Japanese Navy on the U.S. military base at Pearl Harbor dragged the United States into World War II. Every American school child knows the history of that important date.

And every child can recite from memory President Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s famous speech, which begins, “December 7, 1941 — a date which will live in infamy — the United States of America was suddenly and deliberately attacked by naval and air forces of the Empire of Japan.”

While the U.S. was officially neutral in World War II, the country had been engaging in covert activities since the latter part of the 1930s. Subsequent laws like the Lend-Lease Act furthered U.S. involvement well before the infamous date.

So it should come as no surprise that the Federal Bureau of Investigations (FBI) had already drawn up lists of Americans of Japanese, German, and Italian descent in the United States. Within hours of the bombs falling in Pearl Harbor, the FBI began rounding up and detaining Americans of Asian origin.

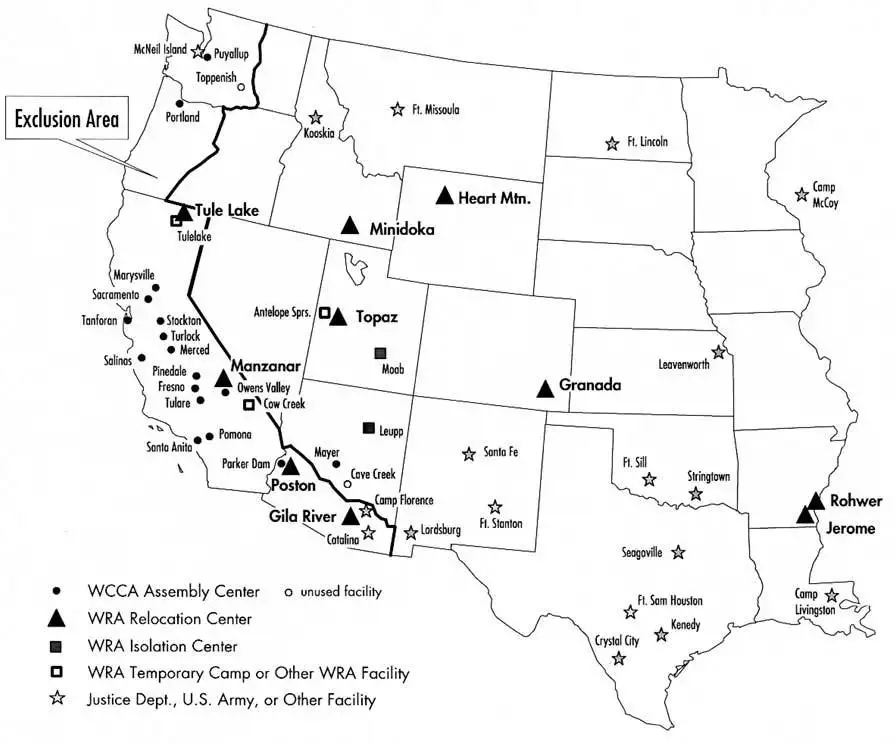

President Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066 in February 1942. This action created the War Relocation Authority (WRA) and the creation of internment camps for individuals of Japanese ancestry, including American citizens. While the government euphemistically called them “relocation centers,” there was no doubt they were nothing other than concentration camps.

In Roosevelt’s mind, the goal was to move individuals who may prove “unloyal” away from the coasts and much further inland in case of an eventual Japanese invasion.

The Japanese internment camp system forced individuals to sell their property and businesses (often at deep losses to white Americans) and relocate far from their homes with nothing more than a single suitcase.

Famed photographer Dorothea Lange was hired by the WRA and the Department of the Interior to photograph the camps, thereby providing an excellent historical record of the tragedy. The historical photos in this article come from her and other photographers and were obtained from the National Archives. Additional historical photos of the Japanese internment camps can be viewed here.

And, as the individuals being rounded up and sent to the desolate Colorado plains found out, they were often un-prepared for the cold and harsh environment they discovered, including brutal summer heat, frigid winter cold, and deep snow.

History of the Japanese Internment Camps in Colorado

The Amache internment camp in Colorado was unique among the U.S. concentration camp system. It was built on private land. It was also built with the support of the State of Colorado.

Of all the politicians in the United States, only Colorado’s Governor, Ralph Carr, opposed the World War II internment camp system. Most governors objected to the relocation of “Japs” within their states. Carr did not.

He lobbied the WRA to build their camp near Granada, Colorado, an old, historic town on the Santa Fe Trail near Bent’s Old Fort and what was historically the end of the line for the Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe Railroad.

Camp Amache was located about two miles southwest of the town of Granada and three miles due south of the Arkansas River. Detainees (actually prisoners) had to carry river stones the three miles to the camp site for building materials.

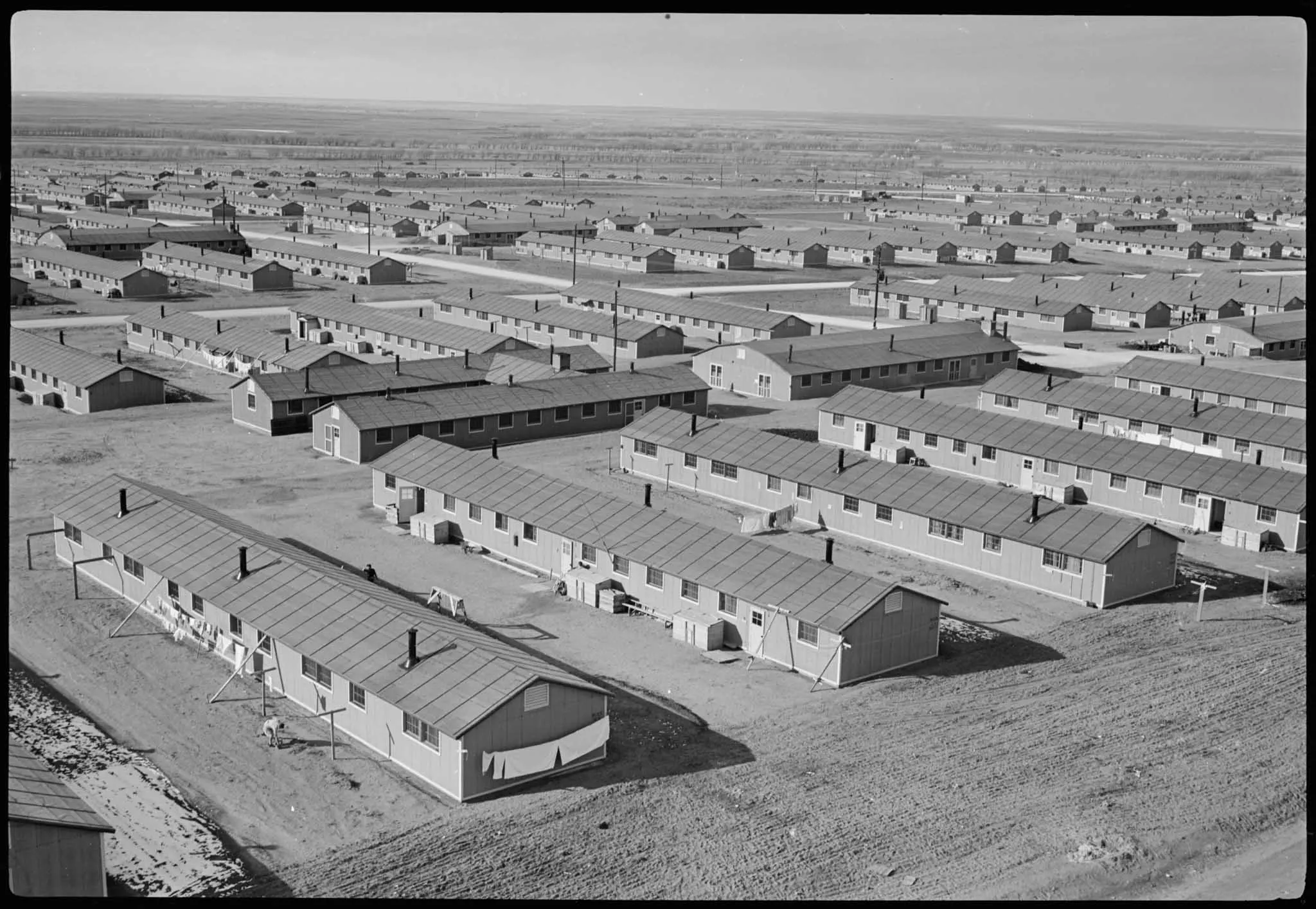

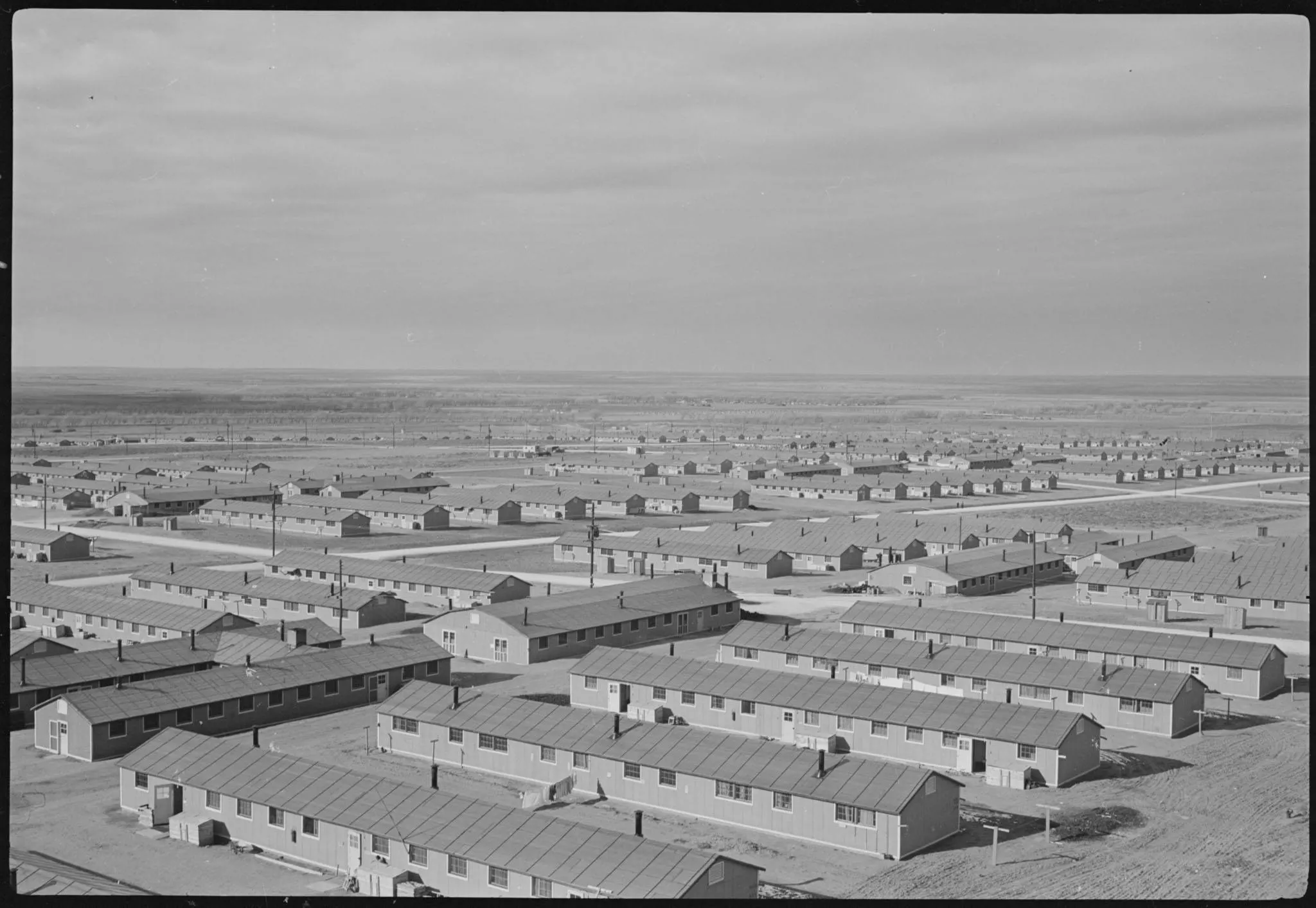

The Granada internment camp hosted over 10,000 people, the vast majority U.S. citizens of Japanese ancestry, on a plot of land that was one square mile (640 acres). Open from August 27, 1942 to October 15, 1945, it was the smallest concentration camp in America, but it was also the 10th largest town in Colorado, dwarfing all other communities in the southeast corner of the state.

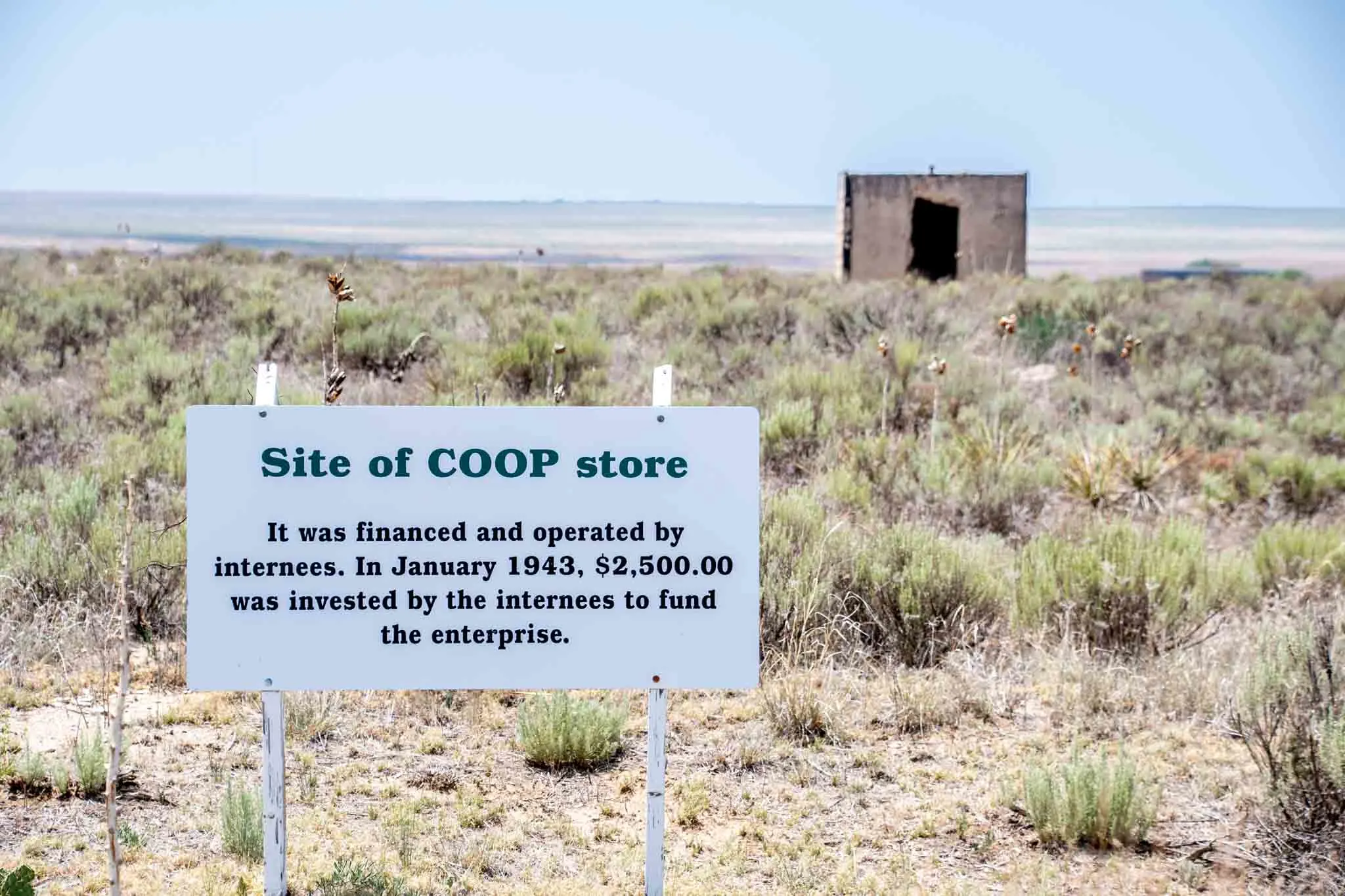

Detainees were sequested in single rooms measuring 20 by 24 feet, wherein all members of an immediate or extended family would be warehoused together. They would work all day in the fields farming and were “paid” a wage of $16 a month (that works out to a wage of about $236 a month by today’s standards). Despite nominal “wages,” the detainees were essentially slave labor for the U.S. war effort engaging in farming or creating war posters in the silkscreen shop.

The Camp Amache farmers grew a large number of crops, including corn, alfalfa, celery, spinach, onions, and beans. These crops then fed the detainees. Surplus supplies were sent to prisoners in other Japanese internment camps, or even to troops overseas.

Detainees at the Granada War Relocation Center often fared better than those in other states. Governor Carr worked hard to ensure they were treated well. And lobbied for them to have privileges like leaving the camp to go shopping in the town of Granada.

While the town was initially wary of their neighbors, a close bond has developed over time. The Amache Japanese-American Relocation Center was owned by the Town of Granada, but in 2022 was transferred to the National Park Service. Much of the work to preserve the site has been undertaken by students at the Granada High School’s Amache Preservation Society (APS) under the leadership of teacher/principal Mr. John Hooper.

To this day, a memorial to Governor Carr can be found in Denver’s Sakura Square, the center of the Japanese-American community in Colorado. A tribute from the community to the one politician in America who stood up for Constitution. And as a youngster growing up in Colorado, I used to drive Carr Street every day. Carr’s spirit of feisty indepdence lives on in the hearts of many Coloradans.

The Granada Relocation Center, which was owned by the town, has been recognized as a National Historic Landmark. In 2022, President Biden signed a bipartisan bill into law designating the property a National Historic Site, now owned and overseen by the National Park Service.

The Legacy of Executive Order 9066

Despite Presdident Roosevelt’s insistence, the actions of Ralph Carr and others demonstrated that some Americans were extremely uncomfortable with the idea of detaining American citizens while denying them due process.

Some in Congress considered overriding Roosevelt. And his own Department of Justice issued a series of of Constitutional and ethical objections to his illegal and unconstitutional actions.

Yet the camps were built. And the camps were occupied. In many many cases, children significantly outnumbered adults. And yes, sometimes children were separated from their families.

Long after the war, there was a strong desire to forget the whole ugly experience. People wanted to look away from the chapter in American history when the government turned its back on the U.S. Constitution. And the “Greatest Generation” quietly ignored one of their greatest failures.

However, decades later, this painful chapter in American history would be dredged up again. Bypartisian legislation was passed in 1988 and signed by President Ronald Raegan at the end of his Administration to address the governments culpability in what happened. The United States Government officially apologized for the illegal action…and agreed to pay financial reparations.

Those financial reparations were later dispersed, along with signed notes of apology from President George H.W. Bush. Then U.S. Attorney General Dick Thornburgh met with survivors and made the presentations…while on his knees.

Visiting Camp Amache

A visit to the Amache relocation camp today is a somber experience. About a half-mile off U.S. highway 50, it is eerily quiet in the camp. Your first impression is the on the vast emptiness of the Colorado plains. Your second impression is of the barren soil and wondering how any farmer could get something to grow here.

On the day of my visit, temperatures were over 100 degrees. There is very little shade at Amache. The few shade trees to be found had actually been planted by the detainees.

The site itself is primitive. The storehouse, the water tower, and the barbed wire fence are all original. A barracks building has been reconstructed on the site and can be toured by arrangement with the Amache Museum.

And a small cemetery plot with a shrine can be found at the far western edge of the camp. The pine trees serving as a wind barrier and the lush grass are the only green to be found anywhere in this desolate brown landscape.

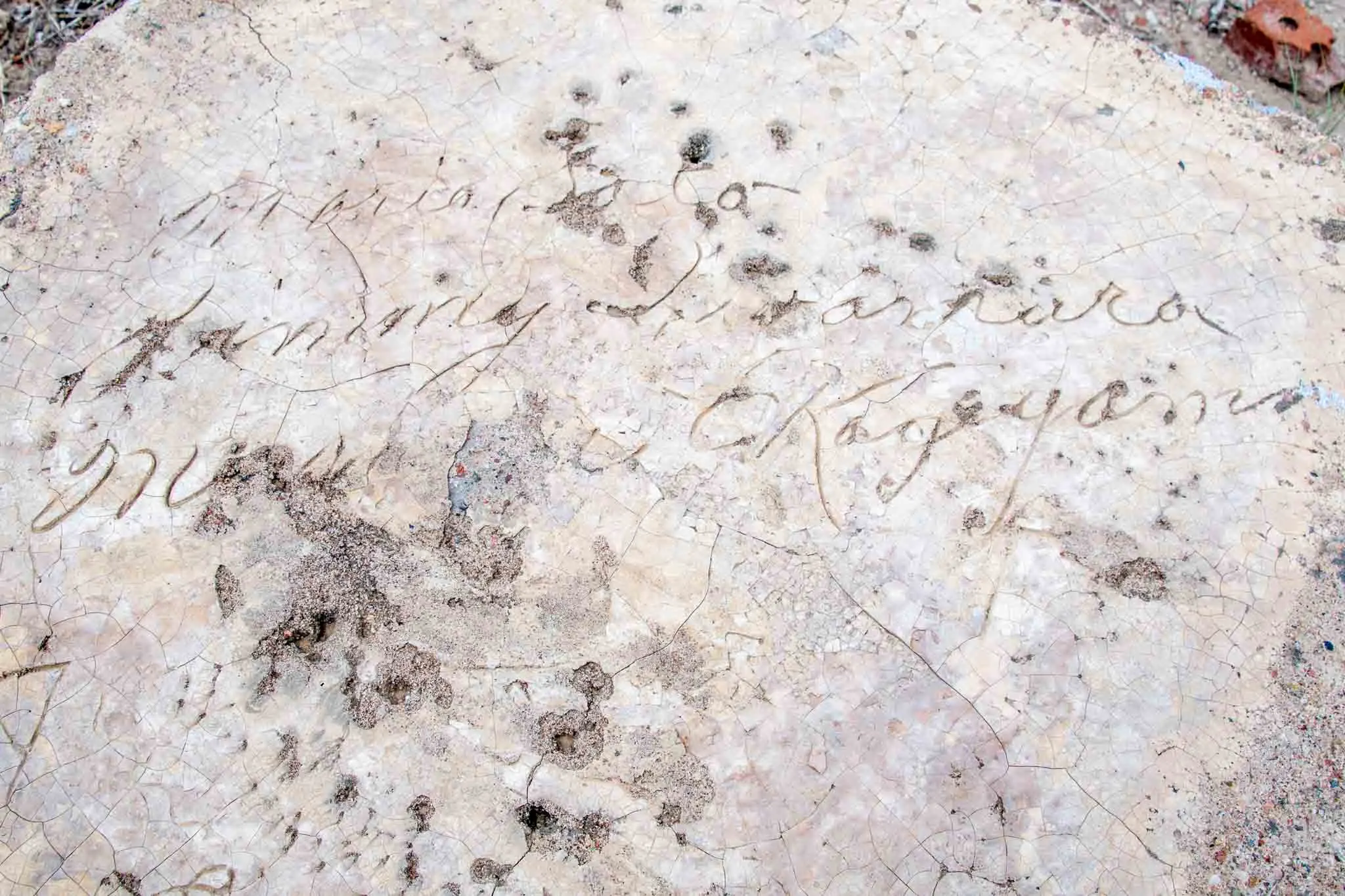

In several places in the camp, you can see where detainees had signed their names in the wet concrete. These permanent reminders of one of America’s dark days were really difficult to look at.

But most disturbing to me where the footprints of the barracks buildings. These concrete foundations supported countless amounts of human suffering…of American suffering. Walking through Amache, I was reminded time and again of how similar these footprint foundations are to the German concentration camps in Europe.

Our Granada Relocation Center visit was a deeply moving and sobering experience. This place serves as a reminder of the past, a warning to the future, and a lesson against succumbing to the twin perils of nationalism and xenophobia.

If you’re visiting Camp Amache, you can’t miss it. Located about two miles west of town, the site is well marked on the south side of highway U.S. 385/50 (the old Santa Fe Trail). The site is accessible essentially 24 hours a day, but with no lights, you’ll want to limit your visit to daytime hours.

These days, the camp is a popular wildlife viewing area. There are lots of animals living on the site, including deer, lizards, rabbits, owls, a hawk and rattlesnakes. We didn’t see any snakes on our visit, but we did see lots of evidence of their presence so step carefully!

The Amache Preservation Society has developed a self-drive route of the site that covers most of the highlights. You can download the map and audio guide here. The audio guide is excellent, but difficult to play from phone (we needed to run it off the computer). And the map shows the camp as it was, not as it is. Pro tip: don’t count the streets, as there are more streets on the map than what you’ll find at the actual site. It takes a little driving around, but you’ll eventually find it all.

There are interpretive signs at each of the major sites to help you locate them and understand what you are seeing. Between the audio guide, map, and signs, you get a good overview of the site.

While in Granada, visitors should also see the Amache Museum, which contains artifacts that were uncovered at the site and also covers the history of the War Relocation Authority. The museum is generally open five days a week in the summer and by special appointment (more details can be found here).

Lance Longwell is a travel writer and photographer who has published Travel Addicts since 2008, making it one of the oldest travel blogs. He is a life-long traveler, having visited all 50 of the United States by the time he graduated high school. Lance has continued his adventures by visiting 70 countries on 5 continents – all in search of the world’s perfect sausage. He’s a passionate foodie and enjoys hot springs and cultural oddities. When he’s not traveling (or writing about travel), you’ll find him photographing his hometown of Philadelphia.

Michiko “Chiko” Bain

Tuesday 22nd of March 2022

Thank you for writing about the Amache camp. I hope you’ll visit Japan someday.

MB Parker, CO

nick

Friday 23rd of September 2022

@Michiko “Chiko” Bain, been to Amache and lived in japan for 18 months

Lance Longwell

Tuesday 22nd of March 2022

Thanks MB. I had the chance to go to Japan for 2 weeks when I was younger. It made an impression on a young child. :) Two years ago we were in the early stages of planning a trip there. Hope we can make the journey sometime soon!