Just 45 minutes from the jazz of Bourbon Street and the spectacle of Jackson Square is another world entirely outside New Orleans—a world of colonnaded mansions, grand antique furnishings, and 300-year-old oaks with Spanish moss whipping in the wind. These are the River Road plantations in Louisiana.

The owners of the antebellum “Big Houses” were some of the wealthiest people in the South. They built successful businesses, acquired massive estates, and bought the finer things in life. But the story of the New Orleans plantations is much more complex than a tale of gorgeous homes and carefully-tended gardens. It is a story with two very different sides that requires acknowledging the dehumanizing conditions of slavery that allowed for the very existence of these impressive estates. Neither simple nor pretty, it is an essential story to hear.

On our 3 day trip to New Orleans, we visited four plantations that approach the story differently.

New Orleans Plantations on the River Road

The Mississippi River is so close you could practically touch it. That’s the feeling you get in the front yards of the plantations here. If not for the levees holding back the water, you might very well be in the river. The same is true along a span of about 70 miles between New Orleans and Baton Rouge known—for obvious reasons—as the River Road.

The plantations near New Orleans date back to the early 1800s. They were built in the economic heyday of the American South, especially when it came to the sugar production that fed this area. One by one, the monumental Southern plantation homes—most in the Greek Revival style, with their beautiful, white columns—took their place along the river.

Although the Big House was often the showpiece of the antebellum plantations, the estates originally had numerous buildings that were integral to their existence. Far from the charming, bucolic view of a verdant plantation that has been romanticized in books and movies, sugarcane plantations were hotbeds of activity, often functioning like independent villages and factories.

The buildings and people moving at a frenetic pace all worked toward one goal: producing crops to make money. The plantations were tightly run organizations, with a collection of quarters for the enslaved, a sugar house (small sugar mill), overseer’s quarters, storage buildings, and more, all operating together to generate income.

After the war, sugar mills became centralized and the ones on individual properties fell into disrepair. The hundreds of mills and thousands of cabins that had housed enslaved workers decayed and were ultimately removed from many properties. Today, there are few left.

Despite the massive economic changes following the Civil War, the plantations remained largely as they were for over 50 years. During the 1920s, the Sugarcane Mosaic Virus nearly collapsed the industry in the southern US and economically devastated many of the Louisiana plantations. Unable to continue with bills and upkeep, many plantation owners abandoned their homes and their land, consigning many Big Houses to disrepair and demolition.

While some plantations could not survive the economic downturn, others looked for new ways to make money such as turning the sugarcane fields into cattle farms. Today, these historic estates are scattered along the River Road, interspersed with housing developments, strip malls, chemical plants, and other signs that life has moved on. At some of them, the majesty of the Big House remains. At others, the stories of the enslaved people who lived and worked there are elevated. Some plantations have both.

Here’s a look at four different experiences we had while visiting the plantations around New Orleans.

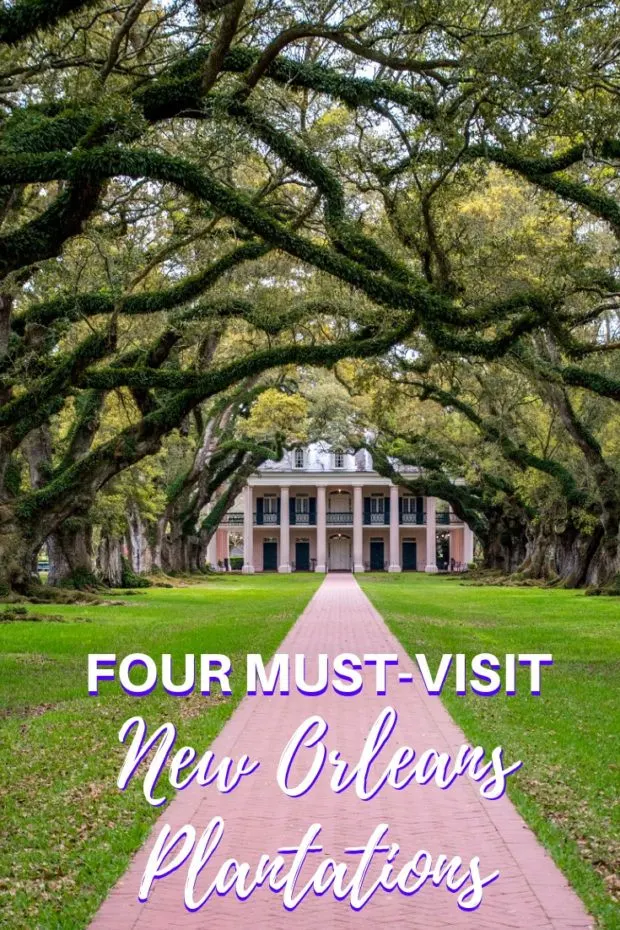

Oak Alley Plantation

Oak Alley is the very picture of what most people imagine as a plantation in the South. It has soaring columns, a wrought iron balcony, and a white exterior meant to look like marble. The quarter mile of oak trees enrobed in Spanish moss and stretching out toward the Mississippi River is one of the most iconic images not just of New Orleans plantations but of plantations anywhere.

Standing under the oaks and gazing back at the house, it’s easy to understand how the idealized view of plantations came to be.

Just a few steps away, the six replica cabins for enslaved workers give a different look at life on the plantation. Three large kettles perched on logs hang from a crossbeam as the primary kitchen the enslaved people were allowed to have at Oak Alley. Inside the cabins, there are wood frame beds with thin mattresses hovering over rope. There are a few simple tables and basic items—a sharp contrast to the massive mansion.

Displays around living quarters and the sick house give some insight into the lives of the enslaved. Not much is known about the personal stories of the 220 men, women, and children who worked on the plantation between 1836 and the Civil War because they were not treated like people. In most instances, a name is all that remains, but Oak Alley is now making an effort to ensure that those names are recognized.

A tour of Oak Alley focuses on the time it was owned by Jacques Roman and his wife Celina. Roman acquired the plantation—then known as the Bon Séjour plantation—from his brother-in-law in 1836. A year later, he began construction of the mansion at the edge of the oak lane that already existed on the property.

Like many of the other plantation owners in Louisiana, the Romans made their money from growing sugarcane. Backbreaking work for those who worked in the fields led to prosperity for the Romans. They flaunted it not only through the size of their house but with the number of enslave people who cared for the home and traveled with the family.

Touring Oak Alley offers an unvarnished look at the dichotomy between the Romans and their enslaved workers. As we walked through the rooms of the Big House, we were struck by the stories about the “connected but separate” lives they led.

In the sitting room, the guide spoke about Celina’s hosting dinners and parties for other members of the local elite. At the same time, she listed what a house worker named Pognon would be doing while the masters were busy entertaining. Dresses representative of what each woman might have worn stood side-by-side.

Similar stories followed about caring for children, taking care of the house, and sleeping. Further emphasizing the tremendous differences between the Romans and those they owned, there is a list showing the prices of items purchased for entertaining compared to the prices paid for the enslaved workers. Seeing that, our tour group let out a collective gasp.

Throughout the mansion, there are period furnishings, sumptuous carpets, and delicate drapes all reflecting a great period of prosperity for the Romans. It was a life of excess and fun. That period didn’t last for long, and Jacques Roman died of tuberculosis in 1848. By 1866, Oak Alley was sold at auction.

The next 50 years brought a series of owners who could not afford the upkeep and maintenance that the grand estate required. In 1925, Andrew and Josephine Stewart purchased it and began undertook restorations. When she died in 1972, Josephine left the historic plantation to the Oak Alley Foundation, which is responsible for opening it to the public.

See other plantations we’ve visited in Nashville, near Charleston, and beyond

Whitney Plantation

Whitney Plantation is the place to go for the slavery story. While other estates have incorporated information about workers on the plantations, Whitney is the first to approach antebellum life entirely from the perspective of enslaved people. Unlike the other plantations where the Big House remains among the central attractions, here, the grounds and the story of the people are the tour. The house is nearly an after-thought.

Information about the owners of Whitney Plantation is captured in the museum that you can visit before the tour begins. Along with offering a detailed look at the history, economics, and realities of growing sugarcane, the museum tells the history of the Haydel family who founded Whitney Plantation.

Ambroise Heidel, a German immigrant, bought the original land for the plantation in 1752 and made the family’s initial fortune growing indigo. By the early 1800s, the main house was built. As of 1820, Heidel’s grandsons Marcellin and Jean Jacques were running one of the most successful sugar plantations in the area, then known as Habitation Haydel.

After Marcellin Haydel died in 1839, his widow bought the plantation at auction and increased production further. During just one season, Habitation Haydel produced a staggering 400,000 pounds of sugar. The success came at a high cost to the hundreds of enslaved people who did the grueling work. The tour is their story.

At the first stop on the Whitney Plantation tour, we met the children. They waited expectantly; they gazed off in the distance. They were unobtrusive in their manner and yet stole the spotlight. The life-sized clay statues were immediately haunting.

The Children of Whitney are a series of sculptures positioned throughout the grounds that are intended to represent the enslaved children who lived and worked on the farm. Their stories come to life through the words of formerly enslaved people who were interviewed for the Federal Writers’ Project (FWP), one of the agencies created by the Works Progress Administration following the Great Depression.

By the time of the interviews in the 1930s, the only formerly enslaved people still living had been children at the time of the Civil War. Thus, the stories reflect the memories of those who spent their childhoods in slavery. To say the displays are moving is an understatement.

From the introduction to the children, we moved on to the Wall of Honor. Inspired by the Vietnam Veterans Memorial—granite in which visitors can see their reflection—the wall shows the names, ages, and skills of more than 350 enslaved people who lived at the plantation. Quotes from the FWP interviews add color about the kinds of things workers experienced on the plantations.

The Whitney has numerous original outbuildings, but its quarters for the enslaved were demolished in the 1970s. Today, cabins from nearby plantations fill that gap and give visitors an idea of the harsh conditions of daily living during slavery on plantations.

In addition to seeing the cabins, there are also vivid stories about the working conditions. Working the sugarcane fields that drove the economic engine of Louisiana was some of the harshest work an enslaved person could do.

From planting to irrigating and weeding, there were tasks to be done year-round, but the worst was grinding season. Most worked around the clock during grinding season, harvesting cane with machetes, hauling, and transferring boiling sugar across a series of large, open kettles. As our tour guide told us, “there was brutality in cotton, but there was death in cane.”

The last stop on the tour was the Big House. One of the best surviving examples of Spanish Creole architecture, it has seven rooms on each level—large but not as grand as the others we visited. Each room has period furnishings, but they are more functional and subdued than the antique filled-rooms we saw elsewhere.

The house is the one place on the plantation where the conversation involved the masters, but even that was balanced. The Children of Whitney remind visitors that enslaved people lived here, too, caring for their masters at all hours of the day and night.

Houmas House

Houmas House Plantation and Gardens is a carnival of colors. There are red poppies, purple pansies, and pink lilies floating in a koi pond by a Japanese tea house. Yes, a Japanese tea house. With a koi pond. It’s not your typical plantation experience.

Visitors don’t come to Houmas House for the slavery story. They come for elegant architecture, fine dining, and the 38 acres of gardens complete with water features and plenty of places to relax and enjoy the surroundings.

The first thing that caught our attention here were the sculptures. There are women in togas, Kabuki dancers, and Greek gods. Nestled among hedges, as the centerpieces of fountains, or just playfully jumping on the lawn, they’re everywhere across the grounds at Houmas House.

Another of its most distinguishing features are the oak trees. Many of the 600-year-old giants were lost when the levee was built and another gave in during Hurricane Harvey, resulting in the beautiful reflecting pool. Those that remain frame the house, combining to give the estate much of its traditional look from the front.

Once part of the largest slave holding in Louisiana, the history of Houmas House is long and highly influenced by the sugarcane trade, as with the other historic estates we visited. Unlike the other estates we saw, its tour focuses on architecture and the many curious antiques inside the Greek Revival-style mansion rather than the story of how it came to be.

The current owner, Kevin Kelly, is the seventh owner of Houmas House and has renovated and transformed it into a destination for weddings, dining, and enjoying the outdoors. Though few of the details of the plantation’s past are highlighted, the stately Big House remains a huge part of the property’s appeal.

The plantation itself dates to the 1700s when the land was purchased from the Houmas Indians who originally occupied the area. Construction on the mansion began around 1810, though it was added to and significantly altered over the years to account for changing tastes and styles as well as modern needs. It has been restored it to its 1840 appearance.

On our tour, we saw the replaced crown mouldings and climbed the swirling, three-story staircase. There is a wall-sized 1848 Louisiana census map that belonged to a previous owner, which was hidden in the attic for 140 years, and original, gold-trimmed china from the same year with the Houmas name.

All the brightly-colored rooms at Houmas House are stuffed with period antiques. There are more typical pieces like a Steinway piano, dark wood tables, and stunning candelabras. From a solid silver statue of Abraham Lincoln cast by the sculptor of Mount Rushmore to portraits of Kelly’s dogs who rule the roost, there are also many exceptional things to see.

Behind the mansion are three restaurants. The casual Café Burnside is open for a quick lunch, and Latil’s Landing is the fine dining restaurant in the property’s original 1700s manor house. We enjoyed breakfast and dinner at the Carriage House Restaurant, which is full of character and unique details.

San Francisco Plantation

Splashed with bright turquoise, pink, and shades of yellow, San Francisco Plantation looked more like the candy-colored houses of Colmar than what we expected from a New Orleans plantation. There was so much going on with the ornate home, we didn’t know where to start.

We saw twin staircases sweeping up to the second floor and twin cisterns topped with Oriental domes on either side of the house. There were bright shutters with lace curtains peeking through and even a string of glimmering gold stars just beneath the roof line. It’s fair to say that nothing about this place was common.

Inside, presenters in period dress brought the details of San Francisco’s history to life.

The origins of San Francisco Plantation date to 1830. Elisée Rillieux, an entrepreneurial free man of color, sold the land he had amassed to Edmond Bozonier Marmillion for an astonishing $100,000 ($2.7 million in today’s money). In debt from day one, Edmond set a precedent that he and his heirs were never really able to shake.

Edmond built a sugar cane plantation and became a successful planter. During the prosperous 1850s, San Francisco’s fortunes looked momentarily bright. Using expert builders and highly skilled enslaved workers, Edmond built and lavishly decorated the estate’s house with painted door panels, faux marbling, faux wood graining, and hand-painted ceilings. The construction and flourishes were expensive, though. When Edmond died in 1856, he left the just-finished home and its tremendous debt to his oldest son Valsin and Valsin’s wife, Louise.

Valsin and Louise raised a family and ran the plantation but never financially prospered. Then came the Civil War, and situations certainly did not improve. It is believed that the very name of the plantation is derived from a comment Valsin made about his extraordinary debt, saying he was sans fruscins, or “without a penny in my pocket.” After Valsin died and Louise and the children left the plantation in 1879, new owners christened it St. Frusquin and, ultimately, San Francisco.

San Francisco Plantation has been open to the public since 1954. Renovations brought back the beautifully painted ceilings and the touches that Edmond had tried to leave as a legacy. The house now reflects the late 1850s, a time when things were good for the owners, as evidenced by the colorful gentlemen’s quarters, brocade fabrics in the bedrooms, and fine china all around.

The situation was not the same for everyone who lived at San Francisco.

An inventory of enslaved people at the plantation in 1856 shows more than 80 workers and their children owned by the Marmillion family. From the 60-year-old blacksmith Ben to the 35-year-old cook Marie Gally described as a “mulatto Creole,” these people endured brutal conditions to ensure that the plantation continued to make money and to keep the family comfortable. Snippets of their lives are seen throughout the tour.

Behind the house is a restored slave cabin from the 1840s of the kind that would have lined the property near the sugarcane field as well as an historic schoolhouse dating from the 1830s. A display gives a glimpse of their meager provisions and the backbreaking work required in the field. There are also details about the Code Noir, the French laws governing slavery in Louisiana.

Specifics are sparse about the enslaved people who made San Francisco run thanks to customs and time. But the quality of their work is obvious and endures in the magnificence of the house they did not get to live in.

Tips for Visiting

There are 10 plantations to visit in the River Parishes. It’s possible to see two or three in one day if you plan your schedule carefully.

In general, tours leave on the hour–and possibly on the half-hour, depending on the property. House tours take about 45 minutes, though you’ll want to leave time to explore the grounds on your own. The guided tour at Whitney Plantation, which includes the house, several memorials, and outbuildings, takes 1.5 hours.

Booking ahead is possible at some of the plantations, including Whitney, Houmas House, and San Francisco. This is particularly advisable if your visit falls on a weekend or during other busy times. If you can’t book ahead and a house tour is a priority, get in line or put your name on the list as soon as you arrive because the capacity is often capped.

We were the guests of Louisiana River Parishes. All opinions are our own.

Laura Longwell is an award-winning travel blogger and photographer. Since founding Travel Addicts in 2008, she has written hundreds of articles that help over 3 million people a year get the most out of their travel. In that time, she has visited nearly 60 countries on 5 continents, often returning to favorite destinations over and over again. She has a deep love of history, uncovering unexpected attractions, and trying all the good food a place has to offer.

In addition to Travel Addicts, Laura runs a site about her hometown of Philadelphia—Guide to Philly—which chronicles unique things to do and places to see around southeastern Pennsylvania. Her travel tips and advice appear across the web.